https://www.europesays.com/uk/39984/ Physicists Have Unlocked the Secret to the Perfect Cup of Coffee, While Using Fewer Beans #coffee #FluidDynamics #PerfectCup #Physics #Science #UK #UnitedKingdom #UniversityOfPennsylvania

Recent searches

Search options

#fluiddynamics

Playful Martian Dust Devils

The Martian atmosphere lacks the density to support tornado storm systems, but vortices are nevertheless a frequent occurrence. As sun-warmed gases rise, neighboring air rushes in, bringing with it any twisted shred of vorticity it carries. Just as an ice skater pulling her arms in spins faster, the gases spin up, forming a dust devil.

In this recent footage from the Perseverance Rover, four dust devils move across the landscape. In the foreground, a tiny one meets up with a big 64-meter dust devil, getting swallowed up in the process. It’s hard to see the details of their crossing, but you can see other vortices meeting and reconnecting here. (Video and image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/LANL/CNES/CNRS/INTA-CSIC/Space Science Institute/ISAE-Supaero/University of Arizona; via Gizmodo)

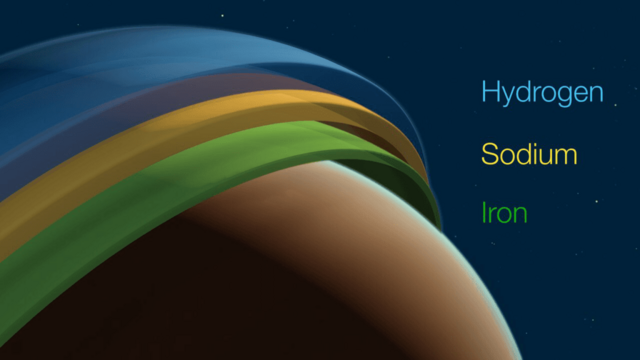

Inside an Alien Atmosphere

Studying the physics of planetary atmospheres is challenging, not least because we only have a handful of examples to work from in our own solar system. So it’s exciting that researchers have unveiled our first look at the 3D structure of an exoplanet‘s atmosphere.

Using ground-based observations, researchers studied WASP-121b, also known as Tylos, an ultra-hot Jupiter that circles its star in only 30 Earth hours. One face of the planet always faces its star while the other faces into space. The team found that the exoplanet has a flow deep in the atmosphere that carries iron from the hot daytime side to the colder night side. Higher up, the atmosphere boasts a super-fast jet-stream that doubles in speed (from an estimated 13 kilometers per second to 26 kilometers per second) as it crosses from the morning terminator to the evening. As one researcher observed, the planet’s everyday winds make Earth’s worst hurricanes look tame. (Image credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser; research credit: J. Seidel et al.; via Gizmodo)

Channeling Espresso

Coffee-making continues to be a rich source for physics insight. The roasting and brewing processes are fertile ground for chemistry, physics, and engineering. Recently, one research group has focused on the phenomenon of channeling, where water follows a preferred path through the coffee grounds rather than seeping uniformly through the grounds. Channeling reduces the amount of coffee extracted in the brew, which is both wasteful and results in a less flavorful cup. By uncovering what mechanics go into channeling, the group hopes to help baristas mitigate the undesirable process, creating a repeatable, efficient, and tasty espresso every time. (Image credit: E. Yavuz; via Ars Technica)

Advancing mathematical physics for fluid motion:

#fluiddynamics #motion #mathematics #physics #research

Researchers claim to have solved Hilbert’s sixth problem by unifying three theories of #FluidDynamics at different levels of granularity:

+ Newton’s laws of motion at the microscopic level where fluids are composed of particles - little billiard balls bopping around and occasionally colliding

+ The Boltzmann equation at the mesoscopic level where the equation considers the likely behavior of a typical particle

+ Euler and #NavierStokes equations at the macroscopic level where the fluids are a single continuous substance

Preprint https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.01800

Flying Without a Rudder

Aircraft typically use a vertical tail to keep the craft from rolling or yawing. Birds, on the other hand, maneuver their wings and tail feathers to counter unwanted motions. Researchers found that the list of necessary adjustments is quite small: just 4 for the tail and 2 for the wings. Implementing those 6 controllable degrees of freedom on their bird-inspired PigeonBot II allowed the biorobot to fly steadily, even in turbulent conditions, without a rudder. Adapting such flight control to the less flexible surfaces of a typical aircraft will take time and creativity, but the savings in mass and drag could be worth it. (Image credit: E. Chang/Lentink Lab; research credit: E. Chang et al.; via Physics Today)

"In the paper, the researchers suggest they have figured out how to unify three physical theories that explain the motion of fluids. [...] This breakthrough won’t change the theories themselves, but it mathematically justifies them and strengthens our confidence that the equations work in the way we think they do."

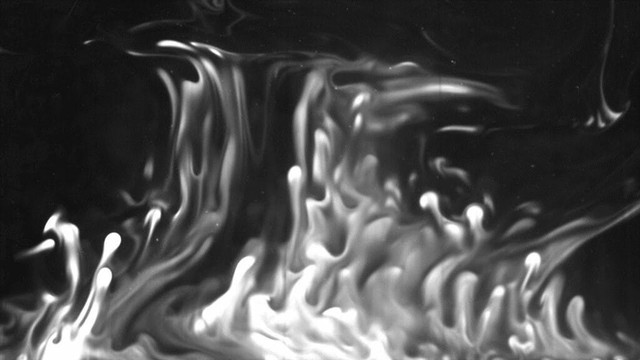

Salt Fingers

Any time a fluid under gravity has areas of differing density, it convects. We’re used to thinking of this in terms of temperature — “hot air rises” — but temperature isn’t the only source of convection. Differences in concentration — like salinity in water — cause convection, too. This video shows a special, more complex case: what happens when there are two sources of density gradient, each of which diffuses at a different rate.

The classic example of this occurs in the ocean, where colder fresher water meets warmer, saltier water (and vice versa). Cold water tends to sink. So does saltier water. But since temperature and salinity move at different speeds, their competing convection takes on a shape that resembles dancing, finger-like plumes as seen here. (Video and image credit: M. Mohaghar et al.)

Arctic Melt

Temperatures in the Arctic are rising faster than elsewhere, triggering more and more melting. Photographer Scott Portelli captured a melting ice shelf protruding into the ocean in this aerial image. Across the top of the frozen landscape, streams and rivers cut through the ice, leading to waterfalls that flood the nearby ocean with freshwater. This meltwater will do more than raise ocean levels; it changes temperature and salinity in these regions, disrupting the convection that keeps our planet healthy. (Image credit: S. Portelli/OPOTY; via Colossal)

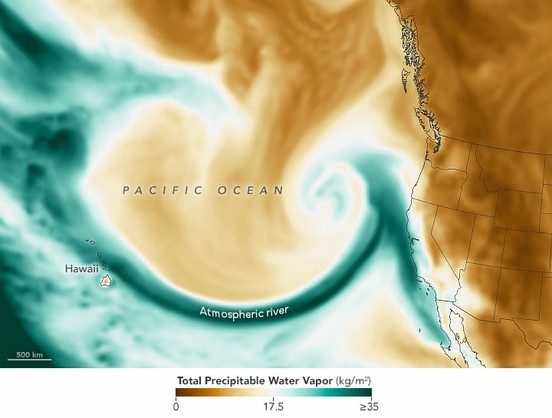

Atmospheric Rivers Raise Temperatures

Atmospheric rivers are narrow streams of moisture-rich air running from tropical regions to mid- or polar latitudes. Though relatively short-lived, they are capable of carrying — and depositing — more water than the largest rivers. But researchers have found that their impact is not measured in water content alone. Instead, a survey of 43 years’ worth of data shows that atmospheric rivers also bring unusually warm temperatures. In some cases, the authors found surface temperatures near an atmospheric river climbed to as high as 15 degrees Celsius above the typical. On average, temperatures were about 5 degrees Celsius higher than expected for the region’s climate.

Several factors raise those temperatures — like the heat released when rising vapor meets cooler air and condenses into liquid — but the biggest effect came from carrying warm tropical temperatures to (usually) cooler regions. (Image credit: L. Dauphin/NASA; research credit: S. Scholz and J. Lora; via Physics Today)

Winter in Chicago

Fresh winter snow blankets Chicago in this satellite image. Over on Lake Michigan, ice dots the coastline out to about 20 kilometers from shore. Darker regions near land mark thinner ice being pushed outward by the wind. Further out, the ice appears white and may be thicker thanks to wind-driven ice piling up. (Image credit: M. Garrison; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Measuring Mucus by Dragging Dead Fish

A fish‘s mucus layer is critical; it protects from pathogens, reduces drag in the water, and, in some cases, protects against predators. But little is known about how mucus could affect terrestrial locomotion in species like the northern snakehead, which can breathe out of the water and move across land. So researchers explored the snakehead’s mucus layer by measuring the force required to drag them (and two other non-terrestrial species) across different surfaces.

The team tested the same, freshly euthanized fish twice: once with its mucus layer intact and again once the mucus was washed off. Unsurprisingly, the fish’s friction was much lower with its mucus. But they also found that the snakehead was slipperier than either the scaled carp or the scale-free catfish. The biologists suggest that the snakehead could have evolved a slipperier mucus to help it move more easily on land, thereby extending the distance it can cover.

As a fluid dynamicist, I think fish mucus sounds like a great new playground for the rheologists among us. (Image and research credit: F. Lopez-Chilel and N. Bressman; via PopSci)

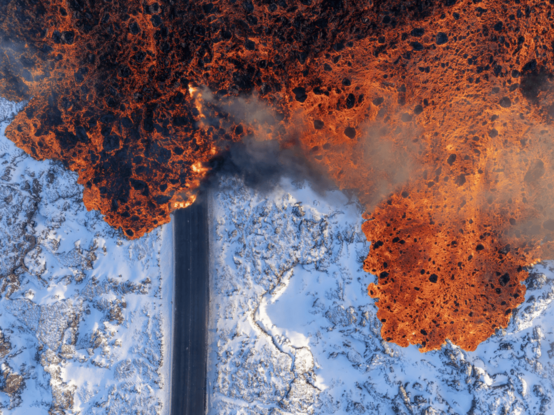

Reclaiming the Land

Lava floods human-made infrastructure on Iceland’s Reykjanes peninsula in this aerial image from photographer Ael Kermarec. Protecting roads and buildings from lava flows is a formidable challenge, but it’s one that researchers are tackling. But the larger and faster the lava flow, the harder infrastructure is to protect. Sometimes our best efforts are simply overwhelmed by nature’s power. (Image credit: A. Kermarec/WNPA; via Colossal)

The Mysterious Flow of Fluid in the Brain

https://www.quantamagazine.org/the-mysterious-flow-of-fluid-in-the-brain-20250326/

Baseball’s Mysterious Rubbing Mud

Since 1938, every ball in Major League Baseball has been covered in a special “rubbing mud” harvested from a secret location in New Jersey. Although the league has tried in the past to replace the mud with an alternative, it’s never stuck. Researchers wondered just what makes this mud so special, so naturally, they brought some to the lab to study its composition and rheology.

The mud consists of clay, silt, and sand with a smattering of organic particles. The make-up was pretty typical of river mud in the region, although researchers noted a drop-off in large particle sizes that probably indicates some sieving. In terms of rheology, the mud is shear-thinning, meaning it behaves a bit like lotion. It sits solidly in the hand until it’s deformed, at which point it smoothly coats the surface as a liquid would.

So how does the mud change the baseballs? The researchers found three effects. First, the mud’s shear-thinning allowed it to fill in any pores or imperfections in the ball’s surface, creating a more uniform surface. Second, the dried mud’s residue doubled the ball’s contact adhesion. And, finally, the occasional large sand particles glued to the ball by the dried mud added friction. As the researchers put it, the rubbing mud “spreads like skin cream and grips like sandpaper.” (Image credit: L. Juarez; research credit: S. Pradeep et al.; via EOS)

Bizarre traveling flame discovery

Steve Mould

#Science #Physics #FluidDynamics #ArtScience

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SqhXQUzVMlQ